Although there are different versions of the story of St. Barbara, Christians in the Middle East and Central Europe still celebrate the early Christian martyr each Dec. 4.

To celebrate St. Barbara’s Day, known as “Eid il-Burbara,” Christians in Jordan, Syria and Lebanon prepare and share a dessert made from boiled wheat, rose water, cinnamon, anise and nuts. This aromatic sweet represents the wheat fields where St. Barbara hid from her father, who kept her locked in a tower because she had converted to Christianity in A.D. 235. Middle Eastern Christians believe that, before her death, St. Barbara escaped her tower prison, and freshly planted wheat fields miraculously rose up around her, concealing her path.

“Often we make this special dish and share it with our family and bring it to our friends,” Munir Bayouk told Catholic News Service. Bayouk works with the Catholic Center for Studies and Media in the Jordanian capital.

Lebanese and Syrians take the celebration a step further, with children dressing up in costumes to commemorate St. Barbara’s flight, creating a Halloween-type disguise. Pumpkins and gourds also are used as decorations.

“We’ve been celebrating ‘Eid iI-Burbara’ since we were kids, and it is such a fun time,” Lebanese psychologist Rima Karam told Catholic News Service. “Children disguise themselves and go from house to house and sing songs for Barbara.”

St. Barbara’s feast marks the beginning of the Christmas decorating season for Lebanese Christians. Lebanese families also plant wheat grains, lentils, chickpeas and other legumes with the idea that in three weeks, the sprouts will be plentiful, accenting the Nativity scene under the Christmas tree.

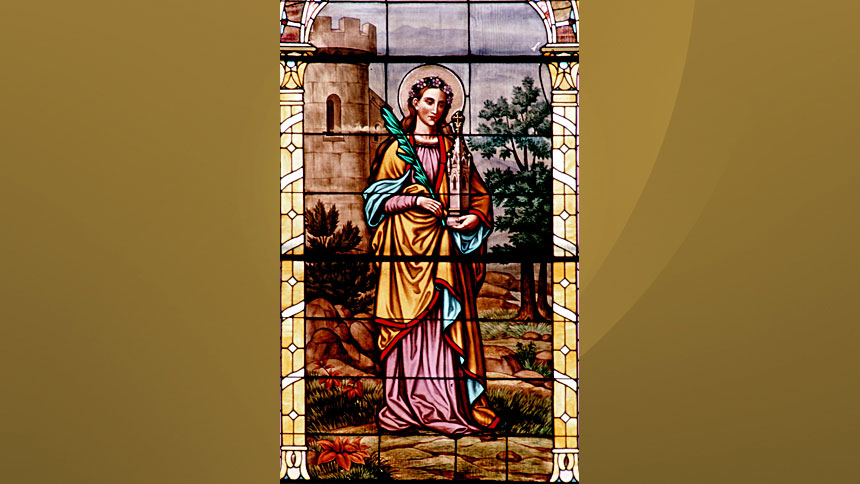

There are different versions of St. Barbara’s story. Legend says she was the beautiful daughter

of a rich and powerful pagan man – some records say in Egypt, others in Turkey. When her father locked her in the tower, she had a window installed made as a symbol of the Trinity. During her time of imprisonment, St. Barbara kept a branch from a cherry tree, which she watered from her cup. On Dec. 4, when her father decapitated her for refusing to renounce Christianity and for rejecting an arranged marriage, the cherry branch blossomed.

Ever since, believers take cherry branches into their homes Dec. 4. If the “Barbara branch” blooms on Christmas, it is considered to bring good fortune. This custom recalls the prophesy in the Old Testament book of Isaiah: The Messiah will spring from the root of Jesse. Christians expectantly await Jesus Christ during Advent, and he will blossom or be born at Christmas. From this tradition comes “Barbarazweig,” the German and Austrian custom of taking branches into the house Dec. 4 with hopes of a bloom on Christmas. In Central Europe, it is believed that the blooming branch signals a promise of marriage in the year ahead.

Many artists’ renditions depict St. Barbara in the tower, holding a chalice or the palm of martyrdom. Some show her with wheat.

Her conduct in the face of persecution and death is seen as a symbol of an unwavering faith and of the determination to defend it, which is why St. Barbara is called upon as an intercessor against thunderstorms, fire risks, fever, the plague and sudden death in general. She is the patron saint of miners and artillery soldiers, and she is also invoked by young, unmarried girls to pick the right husband for them.

The feast of St. Barbara was removed during the 1969 revision of the General Roman Calendar, but is celebrated in various regions.

Families in France’s Provence region germinate wheat on beds of wet cotton in three separate saucers, keeping them moist throughout Advent. When the contents of the three saucers – which symbolize the three persons of the Trinity – are green, they are used to decorate the creche, usually placed under the Christmas tree.

The French saying is “Quand le ble va bien, tout va bien.” or “When the wheat goes well, everything goes well.”